This post is a continuation of the story of Luella Johnston, Sacramento (and California’s) first elected councilwoman. In Part I, I discussed Luella’s civic and political activism in Sacramento, culminating in her successful 1912 campaign for a seat on the Sacramento City Council. In Part II, I discussed her time on the City Council, then called the City Commission. In this third and final part, I discuss her re-election campaign and later years.

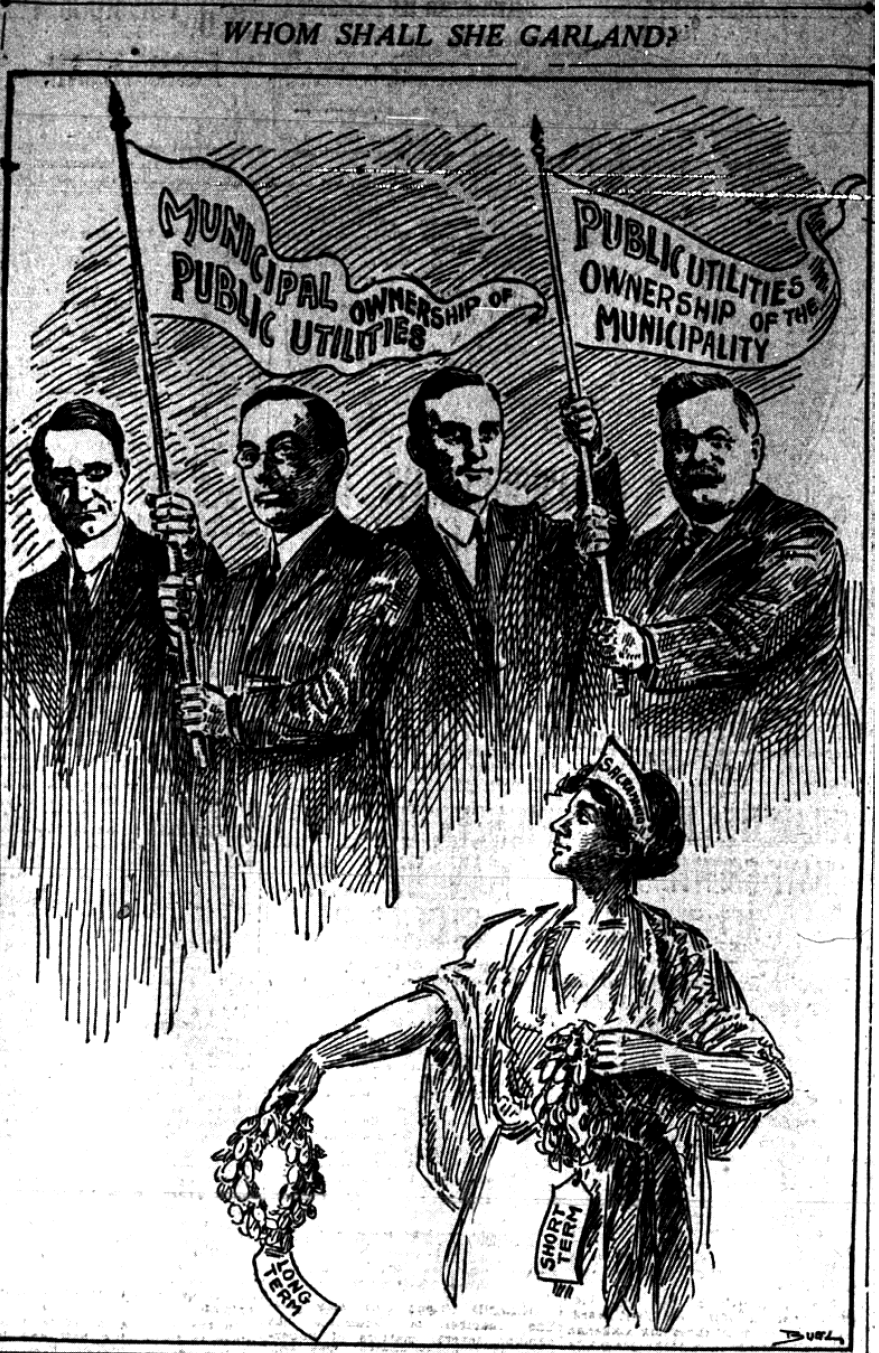

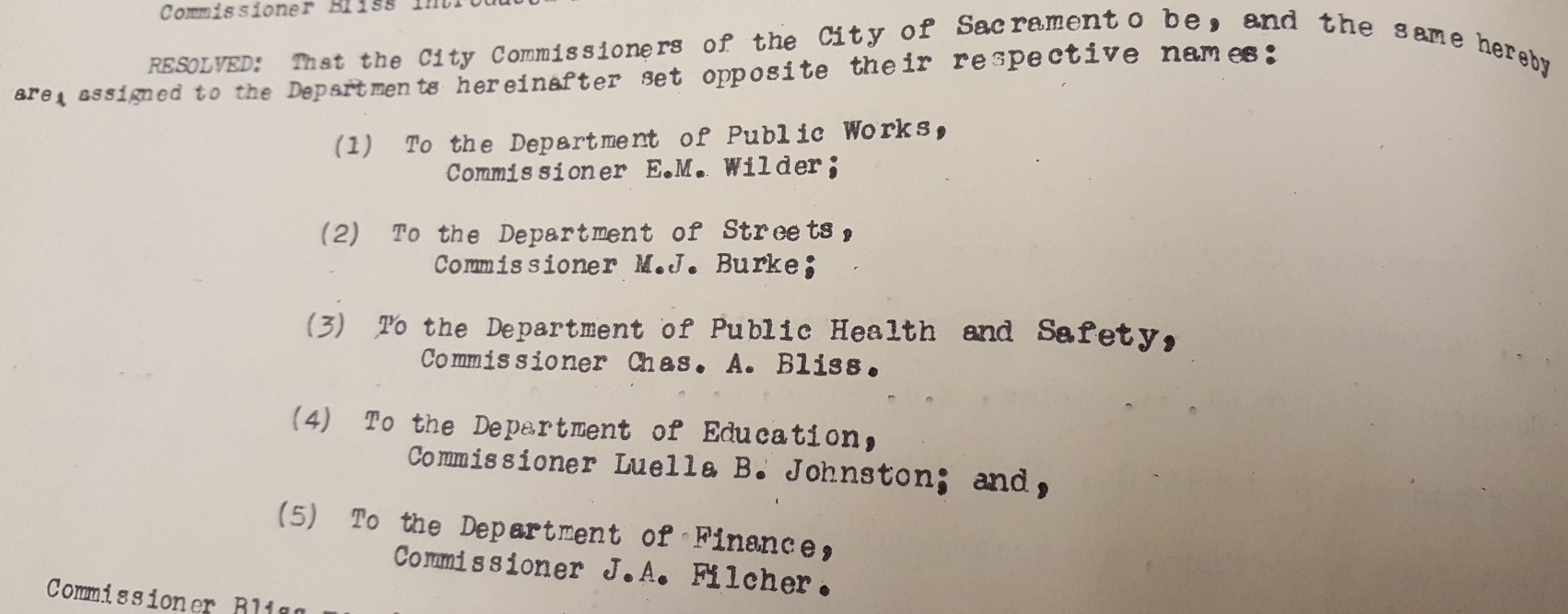

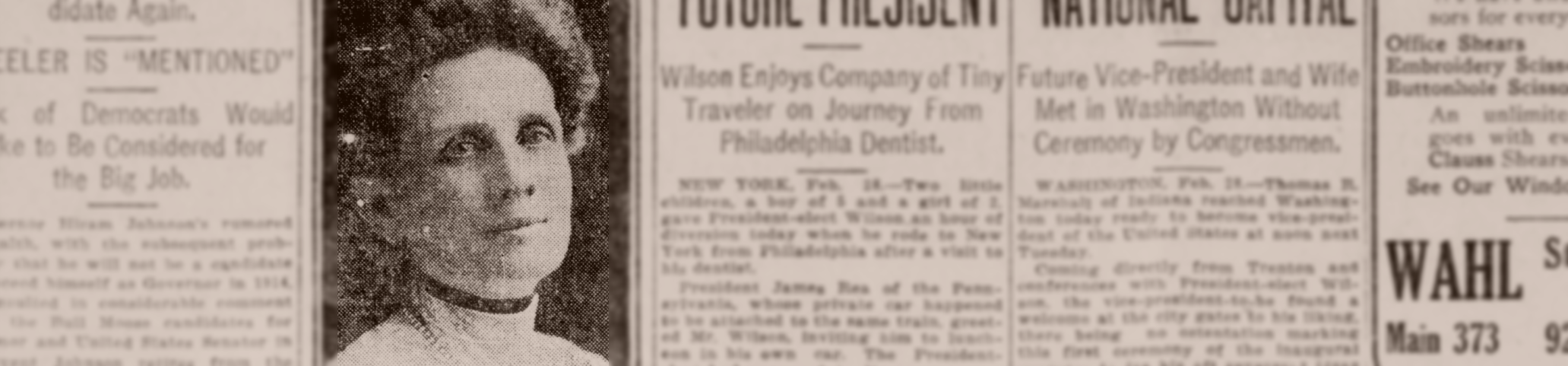

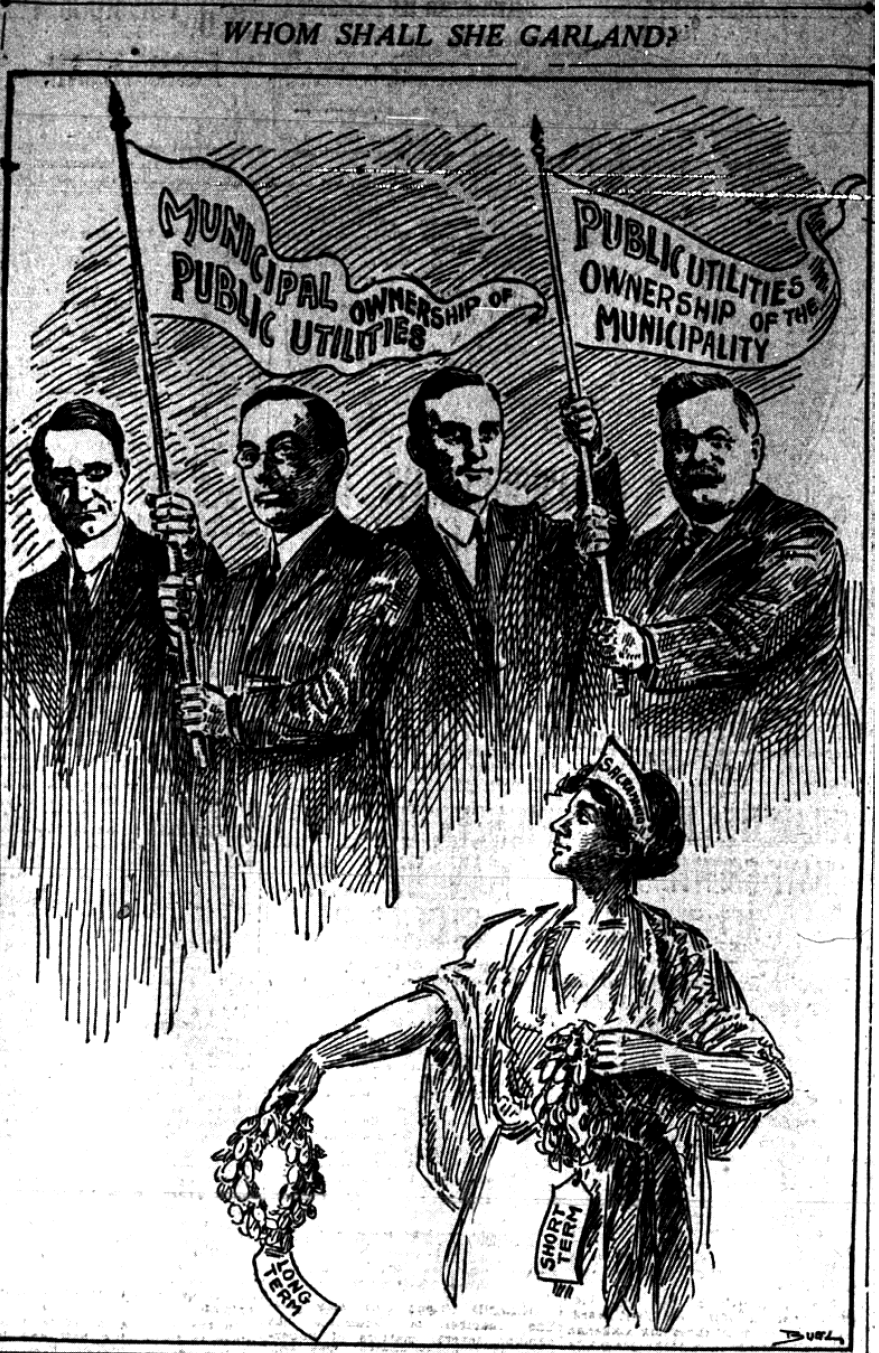

Luella Johnston Campaign Headshot (circa 1912)

Luella Johnston should have been riding high entering into the 1913 campaign season. On the power of the women’s vote in the 1912 election, the anti-corporate Progressives had won every seat of the five-member City Commission governing Sacramento. As part of that wave of reform, Luella was voted into office – the first woman elected to municipal office in California’s history.

In just one year, the reformers had also delivered on much of their agenda. Cronyism seemed to have been reined in. The mighty railcar and utility companies were subjected to greater regulation and rate controls, reducing costs for everyday Sacramentans. And the Commission had proposed and the voters passed several major infrastructure modernization projects, including a levee protection bond that Luella had championed as a candidate.

As the first of her peers to face re-election, Luella was the standard-bearer of the revolution. Luella, proclaimed the Sacramento Bee, “represents the reform and progressive movement which has done so much for the municipality.”

And yet. Despite these successes, Luella’s campaign must have launched with a sense of foreboding.

Sexism would pose an even greater threat in re-election. In 1912 she had won the last of five open seats on the Commission. In 1913, hers was the only seat at issue. “At an election where only one is to be elected,” fretted one of her female supporters, “all the chances favor the election of a man.”

She had also made enemies of some very powerful interests. Early in her 1912 term, she was warned that “if you continue your present course we will see that you stand no chance of re-election.” Nevertheless, she persisted.

That looming threat became very real when the old Political Machine put forth its challenger.

The Machine Strikes Back: Enter E. J. Carraghar

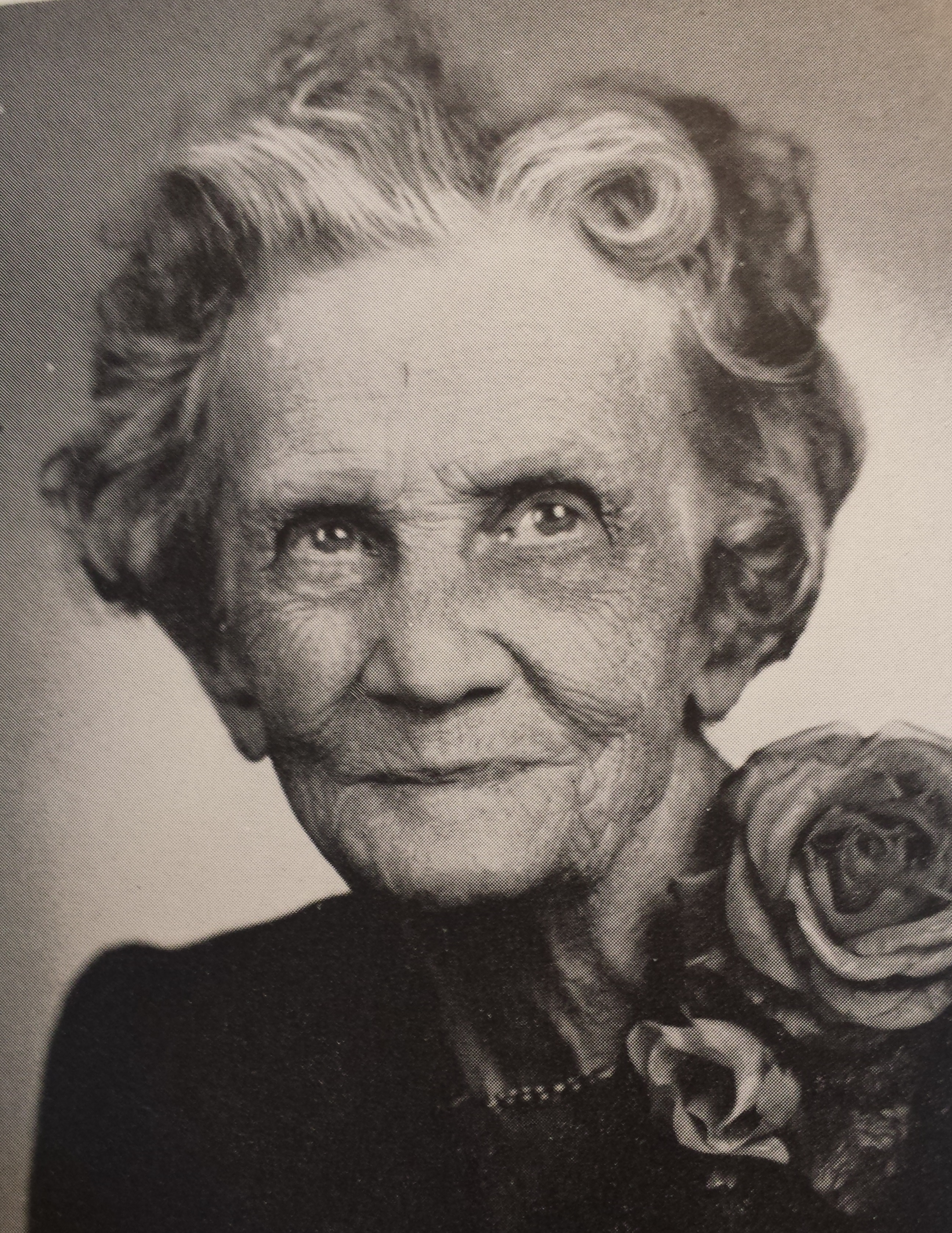

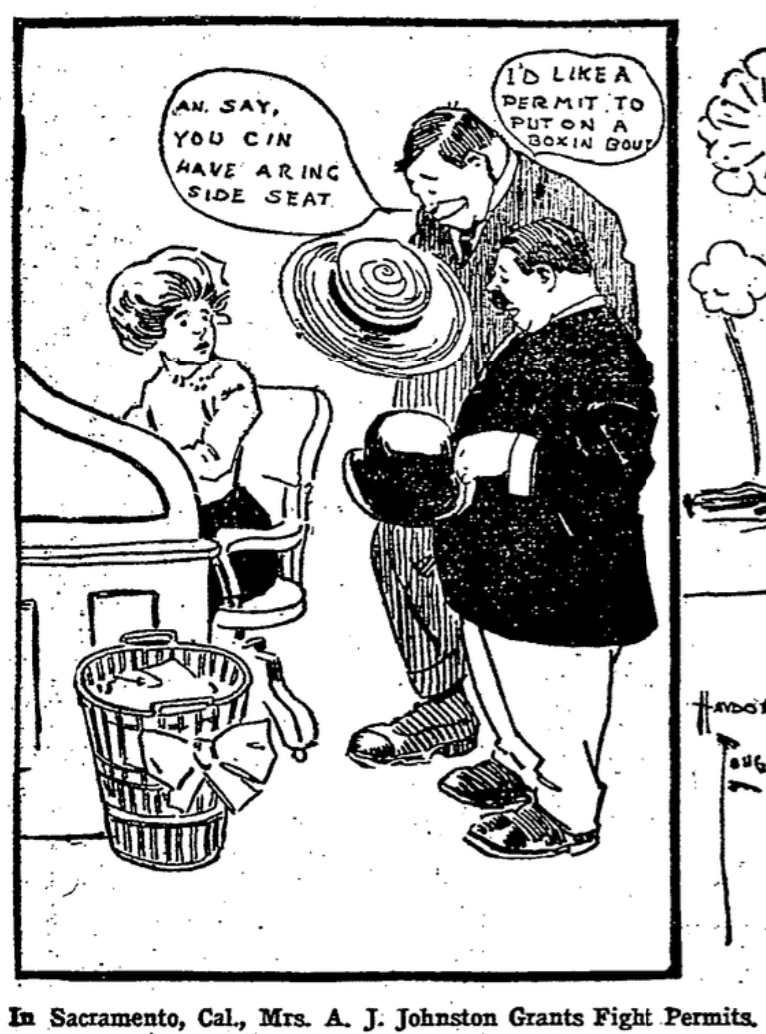

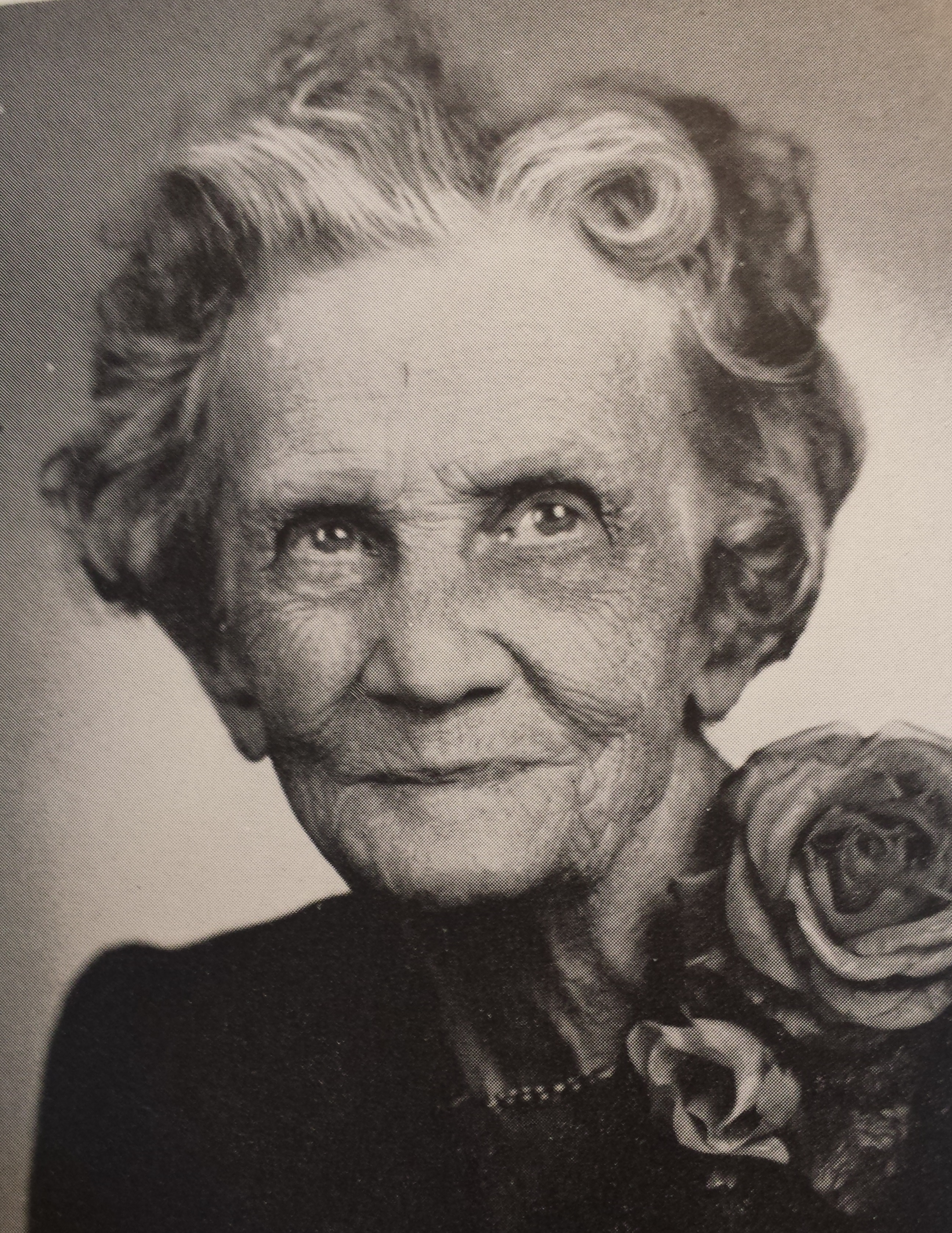

Cartoon of Carraghar, Sacramento Bee (1913)

Edward J. Carraghar was, only one year prior, perhaps the most powerful man in Sacramento. A councilmember until the new charter went into effect in 1912, he was widely seen as the power behind Mayor Beard’s throne in the old City Hall. Under his rule the Southern Pacific, Pacific Gas & Electric, and the city’s public service corporations generally received favorable treatment; they bolstered his reign in return. Carraghar was local Progressives’ bête noire: the “champion,” editorialized the Bee, “of the Machine, the public-service corporations, and the reactionary elements generally.”

If Carraghar won, it would be, the Bee warned, “the opening wedge for the government of this city again by the old crowd. It would herald the beginning of the return to the old condition of Machine and corporation rule.”

Carraghar’s challenge was also personal. In 1912, Luella had terminated his tenure in elective office by narrowly besting him for the last seat on the Commission.

1913 was the rematch. 1913 was the counter-revolution.

The 1913 Campaign: Nasty, Brutish, & Short

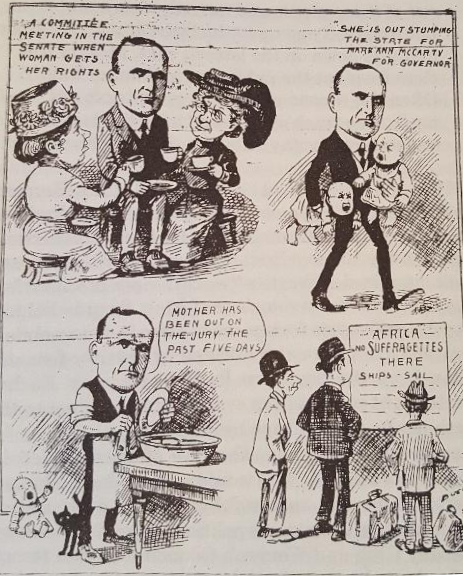

Sacramento Union (1913)

Luella came out of the gate with several important endorsements. The Municipal Voters League, the city’s leading Progressive organization, voted overwhelmingly to support her candidacy. The Bee, too, was amongst her most vocal supporters. Luella, the paper wrote, had been “on the right side and for The People, as against corporate selfishness, graft and improper discrimination.” Finally, the Woman’s Council, that powerful coalition of women’s organizations that Luella had founded almost a decade ago, also pledged its full support: “the women of Sacramento,” declared the Council, “as citizens, voters and taxpayers have a legal and moral right to a representative of their own sex in the city government.”

With her indefatigable style, Luella re-constituted a Women’s Precinct Organization to lead her campaign. She campaigned hard not only on her Progressive bona fides, but also her accomplishments as Commissioner of Education, where she had closed a budget shortfall, addressed student overcrowding, and inaugurated several new children’s parks. It must have been quite the sight, at that time, to see a woman campaigning on her executive and legislative experience. At one campaign stump speech in Oak Park, where Luella had recently inaugurated a new, modern playground, women of the neighborhood reportedly showered her with “three minutes of bouquets of roses.”

But Carraghar was nothing if not a shrewd and battle-tested campaigner. He punched back, hard, hitting Luella wherever she was strongest. “Every trick that political ingenuity can conceive is being used against Mrs. Johnston,” criticized the Bee. “No appeal to prejudice is too base, no lie too brazen, to be rejected in an effort by the old Machine to confuse voters.”

If the Bee was exaggerating, it could only have been by a hair. Time and again the Carraghar camp peddled bald falsehoods to the electorate. For example:

- As a Commissioner, Luella was a consistent vote to regulate the public service corporations whereas Carraghar, as Councilmember, had cut deals favorable to the Southern Pacific and other corporations. In spite of these contrasting histories, his campaign surrogates praised Carraghar as the anti-corporate candidate.

- Luella was an ardent anti-saloon campaigner. Her first political fight was winning a moratorium on new saloons in residential areas. In stark contrast, Carraghar was, himself, a tavern owner. Yet, Carraghar allies implausibly insisted that the “liquor interests” were supporting Luella.

- And the harshest blow of all: Luella was a suffragette, endorsed by the Woman’s Council, and the first woman elected to city office in Sacramento. To counteract this base of support, his camp orchestrated a “Woman’s E. J. Carraghar Club,” which attacked the legitimacy of Luella’s Woman’s Council’s endorsement and warned other women not to be seen as “voting for a woman because she is a woman.”

If the city’s corporations and old power brokers had underestimated the Progressive challenge in 1912, they were not set to repeat that mistake in 1913. According to contemporary accounts, whereas Luella’s was a volunteer-powered campaign, Carraghar’s was backed by “great sums of money,” widely assumed to come from the coffers of the public service corporations.

Unfortunately, Luella herself made a few blunders that her opponent was quick to seize upon. At one point, according to a pro-Carraghar publication, Luella took “an army of small boys away from their studies to distribute anti-Carraghar literature, during school hours.” She also failed to appoint a prominent parks advocate, Mrs. J. Miller, to the parks board, causing a nasty rift within her base in the women’s clubs.

When the Election Day finally arrived, it was a rout: Luella was soundly defeated in every precinct except for the annexed residential neighborhoods.

She took the defeat well, reportedly with a smile on her face as she shook the hands of hundreds of supporters. “When I leave this position,” she said, “it will be with the thought that I have given my best efforts to the city in the limited term of office that I served.”

Three months after Luella’s term officially expired, her former colleagues voted to make her the city’s Truant Officer, responsible for boosting school attendance. Outnumbered for now, Commissioner Carraghar cast a solitary, spiteful protest vote against his former opponent “on the ground that a man should fill the position.”

Progressives still controlled four of the Commission’s five seats, but the 1913 campaign was a dark omen for reformers. The old Machine had proven it was not yet vanquished; it was fighting back.

A Ghost Arises: The 1914 Campaign

Sacramento Bee (1914)

As the city campaign draws to a close, there is heard on the air a sound suspiciously like the rustle of grave clothes. Those bosses whom the people thought had been laid to rest for their long sleep, breaking the bonds that held them, in spectral shape again appear among the living.

Sacramento Union (1914)

Reformers and boss revanchists were set to collide again in 1914, but with even higher stakes. Due to an early resignation on the Commission, two seats instead of one were up for election. Progressive control of the Commission, won a scant two years earlier, was now in jeopardy.

Carraghar pounced. “Give me a man – no, give me two,” he told a meeting of businessmen, “that I may once more get in the saddle and work in your interests.” He was not subtle. “The men who once dictated the politics of Sacramento,” warned the Union, “that unwholesome crew of bosses, are trying to patch up the Machine.”

Emboldened by Luella’s defeat the year before, Sacramento’s business interests could not have been more eager to help.

Long used to a pliant city government, Sacramento’s corporate titans chafed under Commission rule. Dr. E. M. Wilder, the staunchly anti-corporate Commissioner of Public Works up for re-election that year, had emerged as their chief antagonist. He had ordered the Southern Pacific to tear out an unlawfully-constructed rail line, strong-armed the railroad into improving the city’s levees, and cleared the SP out of its prime staging area at the wharfs. He had used his commissionership to undermine Pacific Gas & Electric’s electrical distribution and streetcar monopolies while openly campaigning for full municipal ownership of both. He was the anti-Carraghar.

Completing the good government ticket was O.H. Miller, a prominent developer, who ran for the open Commission seat pledging himself to Wilder’s platform.

Carraghar and his allies put forward their own “Machine” ticket: Thomas Coulter, a hop grower and realty dealer, and Dr. Frederick E. Shaw, a civically-active physician. While never publicly admitted, Coulter and Shaw were generally seen as supported, per the Bee, by the full “power, influence, and money of the Southern Pacific, the Pacific Gas and Electric and other selfish public-service corporations.”

What is beyond dispute is that someone spent heavily to defeat Wilder-Miller, even more than was spent to defeat Luella. “Never before was known such lavish scattering of coin in a Sacramento election,” wrote the Sacramento Bee. Thousands of placards, hundreds of canvassers, and even a few brass bands were trumpeting the Machine candidates. The Sacramento Union estimated at one point that thousands had been spent on the 1914 campaign. (In contrast, Luella only spent $10 on her 1912 campaign.)

When the dust of the election settled, the Machine had once again triumphed. Commissioner Wilder took the loss less gamely than Luella: “It was announced two years ago by the leaders of the old gang in this city that they would get me when my time came and they have indeed done so.” Sacramento’s Progressive revolution was over.

One of the new Commission majority’s first acts: firing Luella Johnston.

Within a few years’ time many of the Commission’s 1912-13 Progressive reforms were undercut or undone. The civil service commission was defunded; health and safety ordinances, including the city’s liquor laws, went unenforced; and regulation of the city’s public service corporations, and chiefly the Southern Pacific and Pacific Gas & Electric, were once again relaxed. By the end of the 1910s, writes local historian William Burg, City Hall had descended “to even worse corruption than under Mayor Beard.”

The Commission model, which had started with such promise, was scrapped by voters in 1921 and replaced with the latest trend in municipal governance: the City Manager form of government we have today.

Later Years

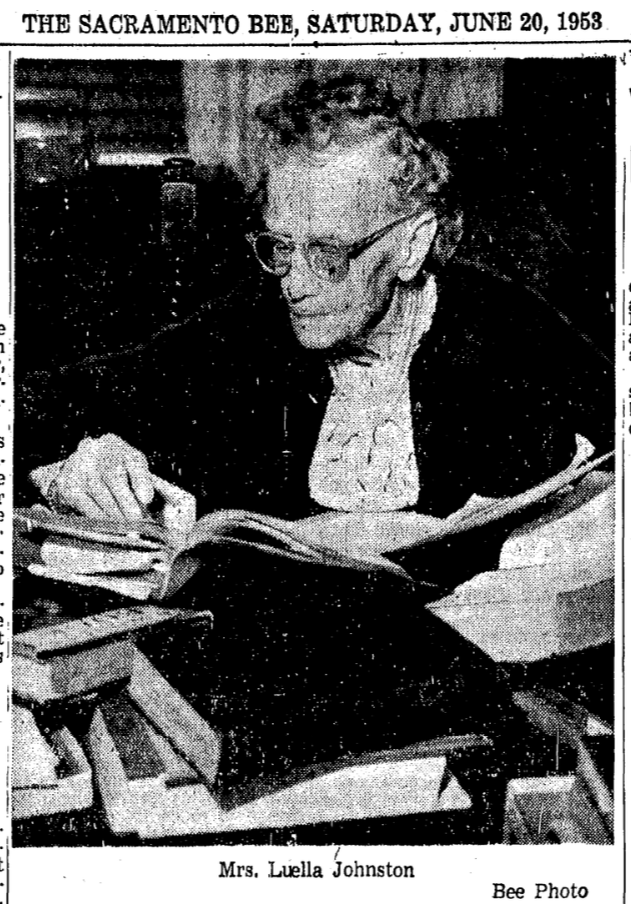

Luella, in her 90s, from Woman’s Council: Silhouette of Service (1955)

Luella quickly bounced back from the Machine’s retribution. Months later, a rare sister-in-politics, Sacramento County’s elected Superintendent of Schools Carolyn Webb, appointed Luella Deputy Superintendent. The assignment was short-lived. Less than a year later, in 1915, Luella would resign in protest over the county pressuring her to take a pay cut to free up funds to hire an additional employee.

In her mid-fifties now, Luella finally seemed content to return to private life. Her name fades from the historical record at this point. From the social notes pages of local newspapers, we know she remained active with both the Tuesday Club and the Woman’s Council, but not leading grand initiatives like she did in earlier years.

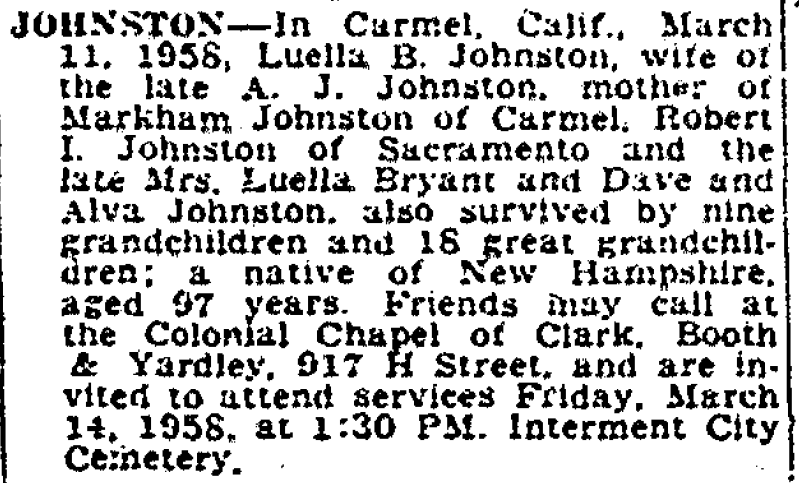

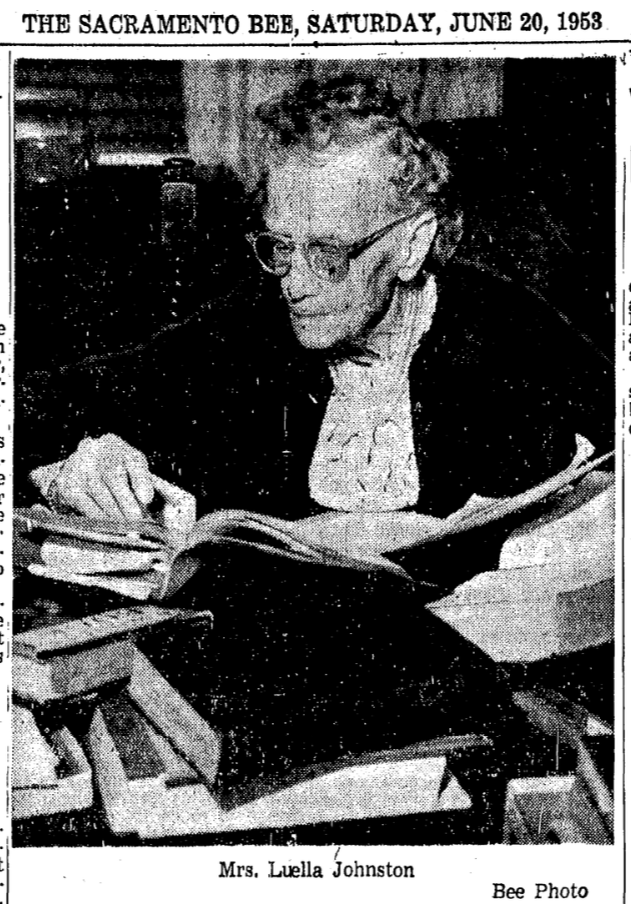

Luella working on her book – Sacramento Bee (1953)

Luella’s passion for public service and education never left her, however. In her twilight years she devoted herself to writing a book to help new immigrants learn English. Tentatively entitled American Folklore, she hoped it would spark a love of reading, particularly for newspapers and magazines. “The most vital thing for any newcomer to this land,” she explained, at age 92, “is to introduce him to the newspapers at the earliest possible moment. Particularly, so he can read about the food that he eats and the clothing he wears.”

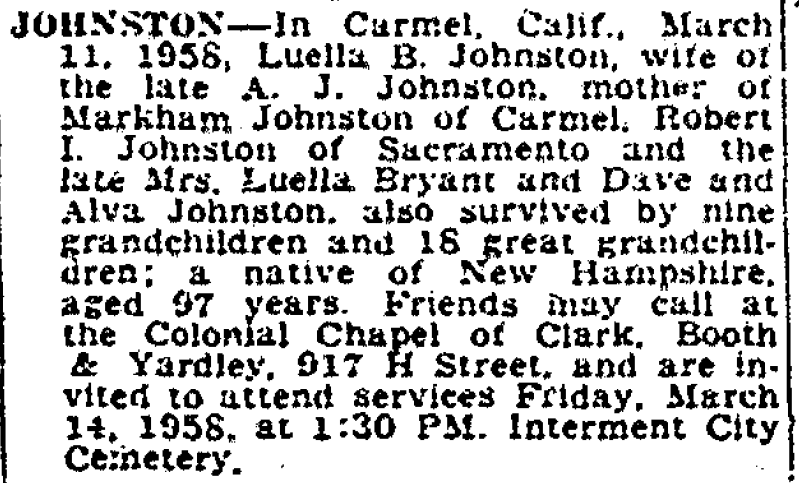

She passed away in 1958, age 97, her book unfinished.

Sacramento Bee Obituary (1958)

Legacy

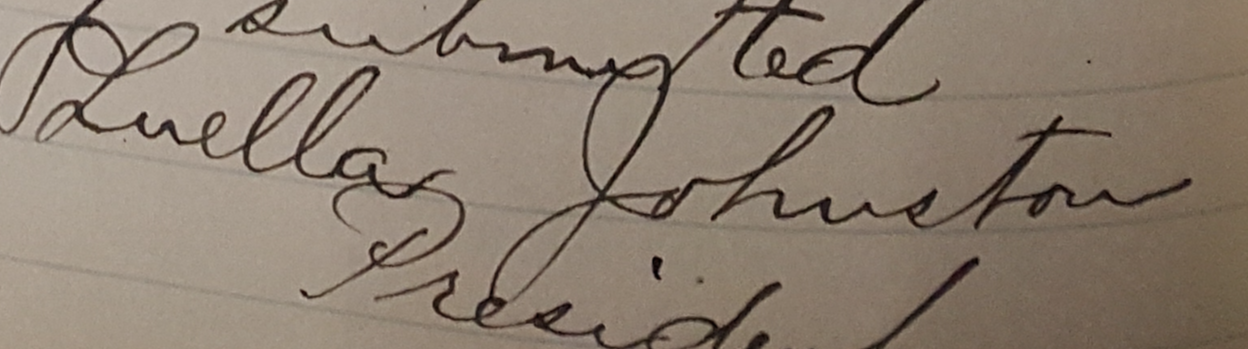

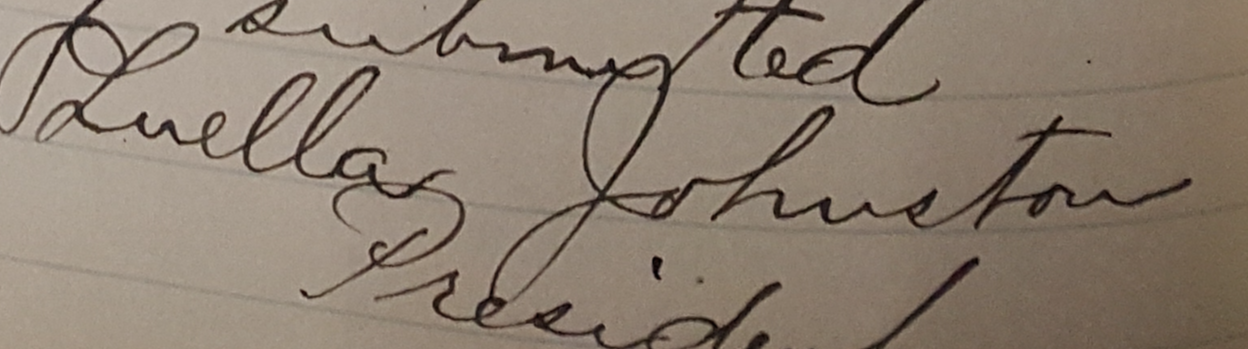

Luella’s Signature (1901)

Luella Johnston played a central role in the social, cultural, and political development of early twentieth century Sacramento. It’s almost overwhelming to describe. She led to prominence the Tuesday Club, which would endure as Sacramento’s premier women’s social club for almost a century. She founded the Woman’s Council, which for decades gave women a seat at the table in making and passing municipal public policy. She was an early education reformer whose successes from the 1900s and 1910s, wrote the Sacramento Union in 1948, still remained decades later “as monuments to the efforts of one frail woman who probably never weighed 100 pounds in her life.” She was integral to the rise of the City’s Progressive moment, which, although short-lived, produced infrastructure improvements (like the Yolo Bypass) and policies (like municipal ownership of electrical distribution, which decades later would evolve into SMUD) that live with us today. She was a crusader for women’s rights in a hostile era and earned the laurel of being the first woman elected to municipal office in California. (And, quite possibly, of any major city in the United States.)

Her accomplishments seem to be too many for a single life.

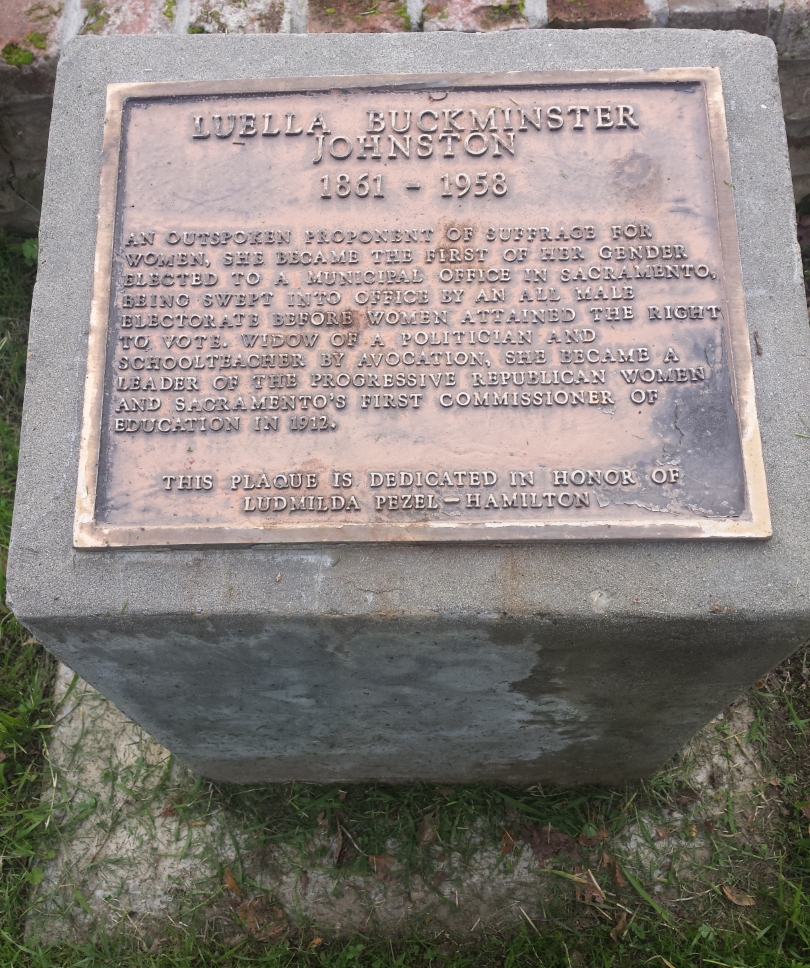

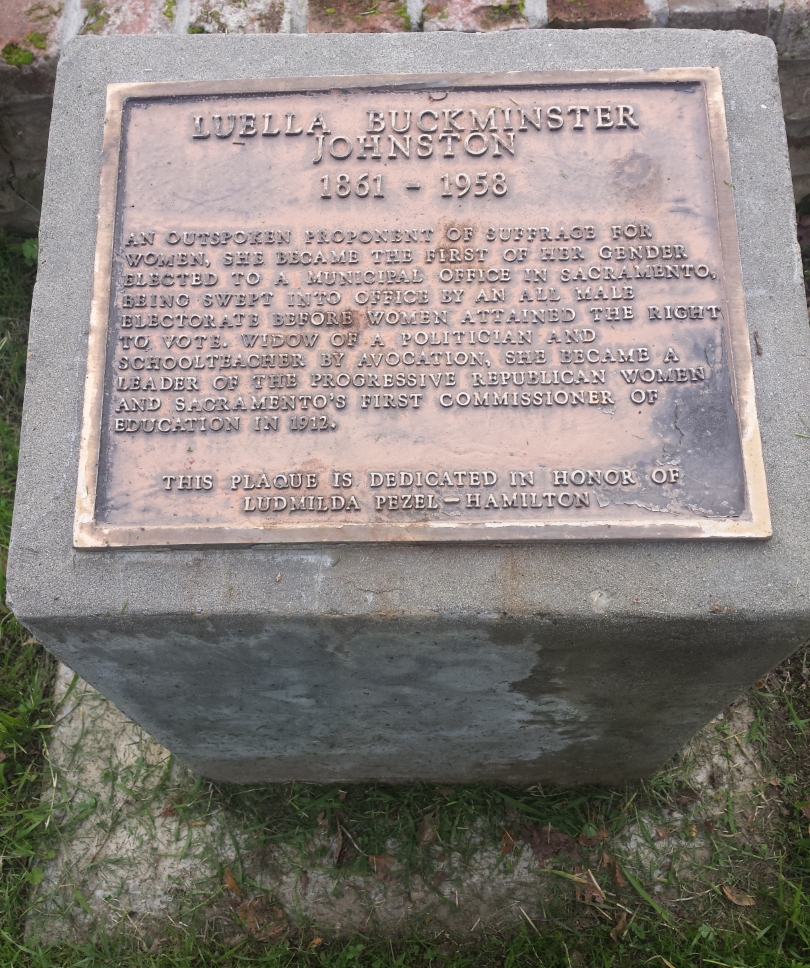

Sadly, as far as I am aware, there are no memorials to Luella in Sacramento. Neither Johnston Park, Community Center, Pool, nor Road refer to Luella Johnston, but rather to Carl Johnston – an unrelated, early North Sacramento developer. The most I have found honoring her is a small (and sadly inaccurate – her 1913 election was the first in which California women could vote) plaque at her gravesite in the Old City Cemetery.

Old Cemetery Plaque

I can’t help but feel that is a serious oversight. It’s important to honor the city heroes who helped make Sacramento what it is today, lest they be forgotten, like Luella. It’s also important to correct omissions regarding women’s accomplishments, which are sometimes overlooked or minimized in history books.

Imagine for a moment if the Old City Council chambers where she used to serve, today nameless, were re-christened the Luella Johnston Council Chambers. In the march for gender equality, so relevant in the news today, I think it would be a beautiful reminder of how far we’ve come and how far we’ve yet to go.

***

Abridged Bibliography

In putting together this account of early 1910s Sacramento political history, Luella’s last campaign, and her later years, I drew heavily on, and am indebted to, the following sources:

Over the last several years, the conversation over who holds power in the upper echelons of the private sector and government have increasingly focused on the lack of women and people of color. Indeed, the University of California, Davis produced

Over the last several years, the conversation over who holds power in the upper echelons of the private sector and government have increasingly focused on the lack of women and people of color. Indeed, the University of California, Davis produced